The Teatro Real presents a wonderfully un-German new production of Germany’s fateful work. This is mainly due to the musical side, as Pablos Heras-Casado on the podium explores the subtleties and nuances of the score in great detail.

The title of the new production, which will also be performed at the Copenhagen Opera and the National Theatre in Brno, has been given the Spanish title: ‘Los maestros cantores de Núremberg’.

Yet ‘Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg’ is actually a German work of destiny in a negative sense. Marches, triumphal music, resounding “Heil”-shouts. All securely wrapped up in the colourful atmosphere of medieval Nuremberg, recorded and then given a grandiose and convincing variation and new meaning by the great dazzler Wagner. Flavoured with Bachian counterpoint and a Martin Luther chorale as musical accompaniment, the little Saxon remained true to himself even in his late works, when old material (see ‘Lohengrin’, ‘Tannhäuser’, ‘Flying Dutchman’, among others) is used for new visions.

Nonetheless, from a musical point of view, the ‘Meistersinger’ are not to be despised. In fact, they are a masterpiece. As is well known, the piece only developed into a ‘real’ work of destiny through its Bayreuth reception history, culminating in the Second World War, where only the ‘Meistersinger’ was on the programme for tired soldiers on home leave at the ‘War Festival Bayreuth’ in 1944. Prior to this, Adolf Hitler (usually deliberately dressed in civilian tails) had made reverent and reserved appearances at the festival.

However, due to the end of the ‘Meistersinger’ with the at least problematic final speech by the main protagonist (‘Habt Acht! Uns dräuen üble Streich…’), the problems also lie in the piece itself. And this immanence makes it difficult, as Laurent Pelly‘s directorial work now presented revealed.

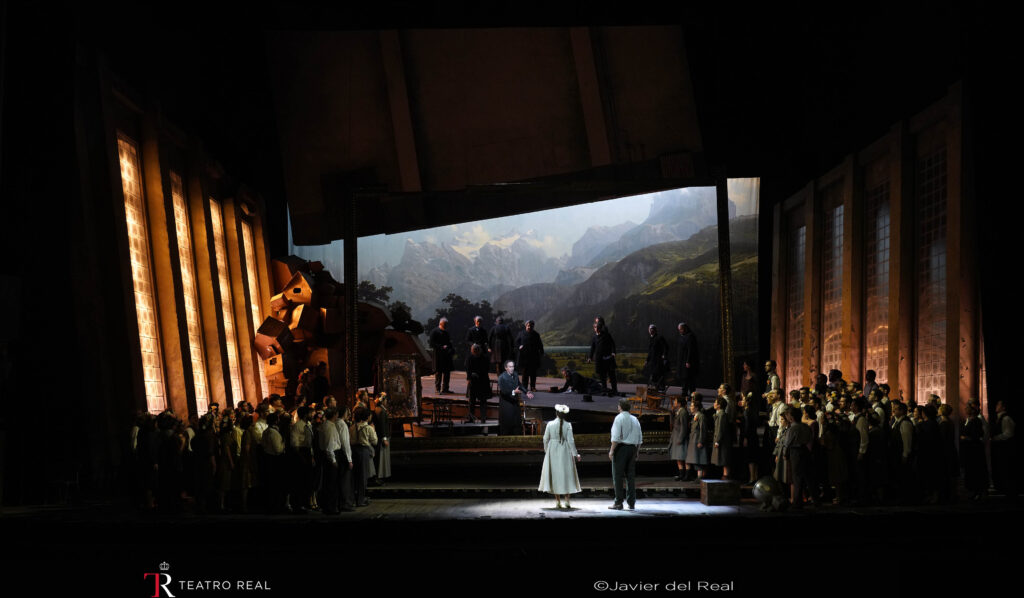

The enterprising theatre man and opera director from Paris sets the ‘Maestros cantores’, the bourgeois craft guild of poets and singers in the Middle Ages that went down in history with Hans Sachs as a cobbler, in a somehow dystopian setting (set by Caroline Ginet) that could be found anywhere. The space, with walls with raised window fronts on the left and right throughout the acts, is out of joint and askew. Whether church, singing parlour or lecture hall: what the hall was once used for before the crisis remains open and vague.

After the opening chorale at the beginning of the first act, the mighty, radiantly singing chorus (rehearsed by José Luis Basso) exoduses in drab, ashen clothing (costumed by the director). One might still suspect that a ‘Prügelfuge’ staged as a pogrom at the end of the second act could have been shown here in anticipation of the deportation or flight of Jewish refugees from Hitler’s Germany. But far from it: Pelly deliberately avoids allusions and references to German history throughout. For example, the houses used as stage backdrops are cardboard boxes that end up in the pile of history in the corner of the stage after the beating scene.

And therein lies the strength of the directorial idea of viewing marginalisation, discrimination and persecution as a universal component that can occur anywhere. However, this can certainly only be credibly achieved outside Germany. A production that detaches itself from the history of the work’s reception (even from the end of the ‘Meistersinger’ itself) cannot be convincing in Bayreuth, where it would only come across as clean washing.

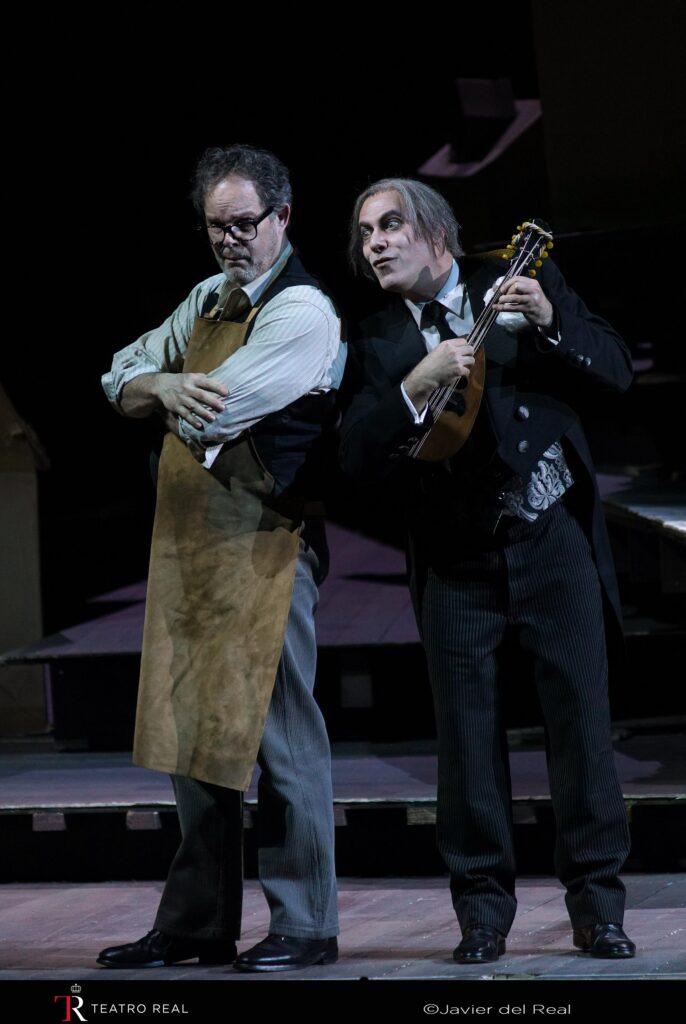

In Madrid, however, a production was staged which, apart from David (Sebastian Kohlhepp with wonderful text comprehensibility and crystal-clear intonation), had no other German singers on the cast list. Only the Beckmesser harp, specially borrowed from Bayreuth, bore witness to the heavy German tradition. In view of the fact that it is singers with a German passport who are engaged by major opera houses around the world for the great German repertoire, this was a small peculiarity that pointed the finger: relaxed and light is not possible in Germany – the ‘Meistersinger’ must go out into the world for this!

The effect was refreshing, light and liberating without any aftertaste. What’s more, Pablo Heras-Casado conducted the Teatro Real’s titular orchestra with a musical interpretation that was so fluid and varied that it deliberately avoided grand outbursts and triumphant sounds. The virility with which the overture sounded in the velvety, softly graded acoustics of the Teatro Real, with its slender conducting and mannered filigree, made one sit up and take notice. Repeatedly moderating interventions, such as in the ‘Wach auf, es nahet gen den Tag’, testified to a jointly developed overall approach, which was also intended to emphasise the immanent artistic and cultural criticism of the innovator Wagner. A delight!

After all, breaking up the Meistersinger Guild, which had become ossified in pointless rituals, would also have been Wagner’s own wish. Walther von Stolzing’s ‘Preislied’ (performed by Tomislav Mužek, who was born in Germany but grew up in Croatia, in a flooding, lyrical and beautifully nuanced way) was seen by the composer himself as an innovative, romantic song with an impulse of renewal. The production follows this interpretation through Urs Schönebaum‘s lighting, which briefly bathes the hall in a warm reddish colour for Stolzing’s melting aria.

However, as August Everding once emphasised, Beckmesser’s music is actually the more innovative (from today’s perspective). Both the director and the composer are mistaken in this respect, as the Stolzing aria (once beautifully performed by Katharina Wagner in Bayreuth) is essentially nothing more than conventional german folk music (‘Volksmusik’) à la Florian Silbereisen and Helene Fischer.

A half-baked ending is the second weak point of the new production: the blissful red light suddenly goes out when Hans Sachs begins his final speech and the Meistersinger look startled for a moment. Finally, David and Magdalene (Anna Lapkovskaja with a warm timbre and a guttural touch) bashfully draw the final curtain. However, ‘Volk und Verbände’ in front of a romantic Alpine landscape had previously been very impressed by the nationalistic nonsense that Wagner put into Sachs’ mouth. Presenting a clearer stance in one direction or the other, which clearly emerges from the central theme of the production, would have been more fruitful in terms of craftsmanship and content. As it is, however, an aftertaste of irrelevance remains, which arises from the arbitrariness of the possibilities.

Furthermore, a cast list of high quality: Gerald Finley‘s Hans Sachs is precise, gripping and clear right to the end which is rare. His baritone is supple and lyrical right to the end, but full of space, which corresponds well to the director’s idea with his musical interpretation. The ‘Wahn’-monologue and the ‘Flieder’-aria are musically very convincing, although – as in the large chorus and ensemble scenes – the characterisation remains all too static and at times reliant on arbitrary operatic gestures.

In contrast, Leigh Melrose displays unbridled enthusiasm as the smarmy, slimy Beckmesser, who receives the most applause on the day of the premiere with equally musical emphasis, but singing with great precision and accuracy. Nicole Chevalier‘s Eva is able to score points with her youthful intonation and lyrical difference, which in the third act makes a significant contribution to the overall harmonious picture of the impressively sung quintet.

In the other roles, Jongmin Park was convincing as the aged Pogner with his confidently sung bass and José Antonio López as Fritz Kothner, who sang with great assurance. At the end there was much applause for all involved.

Further performances on 28 April and 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 21 and 25 May 2024.