My Dear Swan: In Hanover, Richard Brunel presents a bird-laden Lohengrin of remarkable depth and complexity, offering the most comprehensive interpretation of all dimensions and characters. Unfortunately, Stephan Zilias at the podium of the Staatsorchester Hannover manages little more than a patchy, shapeless musical accompaniment (performance of 21/09/25).

This first premiere under the new General Director Bodo Busse is a co-production with the Opéra National de Lyon. Its director and artistic head, Brunel, has come to Lower Saxony to present his reading of the problematic themes surrounding the Swan Knight—caught between unconditional obedience (“the forbidden question”) and German militarism. And how! Rarely has such an expansive interpretation been seen on stage, realised with such artistic sophistication, dramaturgical precision, and vibrant diversity—even down to the tiniest detail.

To mention the only caveat up front: this direction might be a bit much—perhaps too dense or too intellectual—for unprepared visitors, underpinned as it is by a weighty theoretical framework.

“Mein lieber Schwan (my dear swan)”—the famous phrase from Act III that has entered everyday language as a proverbial exclamation of astonishment, much like the ubiquitous Bridal Chorus from the same act—attests to the far-reaching cultural impact of this romantic opera, rich in choral tableaux and striking arias. A work that, not without reason, was first critically examined in Heinrich Mann’s „Der Untertan (The Loyal Subject)“ in the context of German authoritarianism and blind obedience.

It is thus all the more appropriate and welcome that the French director Brunel approaches this aspect head-on. The textually repugnant passages—especially in the choruses (“For German land, the German sword…”)—are not dismissed as harmless local colour (as so often done in other productions), but are deliberately and pointedly embedded into the overarching context. In this sense, “Mein lieber Schwan” becomes an expression of admiration: what an impressive piece of directing!

In Brunel’s staging, Lohengrin is a witness to the murder of Gottfried. The backstory is presented immediately on Anouk Dell’Aiera’s revolving stage. Ortrud smothers Elsa’s brother with a pillow. Gottfried, locked up and sitting with a birdcage on his bed, clings to hope for rescue while drawing friendly baby birds on the wall. Yet, as the stage turns, these drawings evolve into torn, grotesque bird-souls sketched around Ortrud’s balcony. In despair, Lohengrin carries away Gottfried’s body.

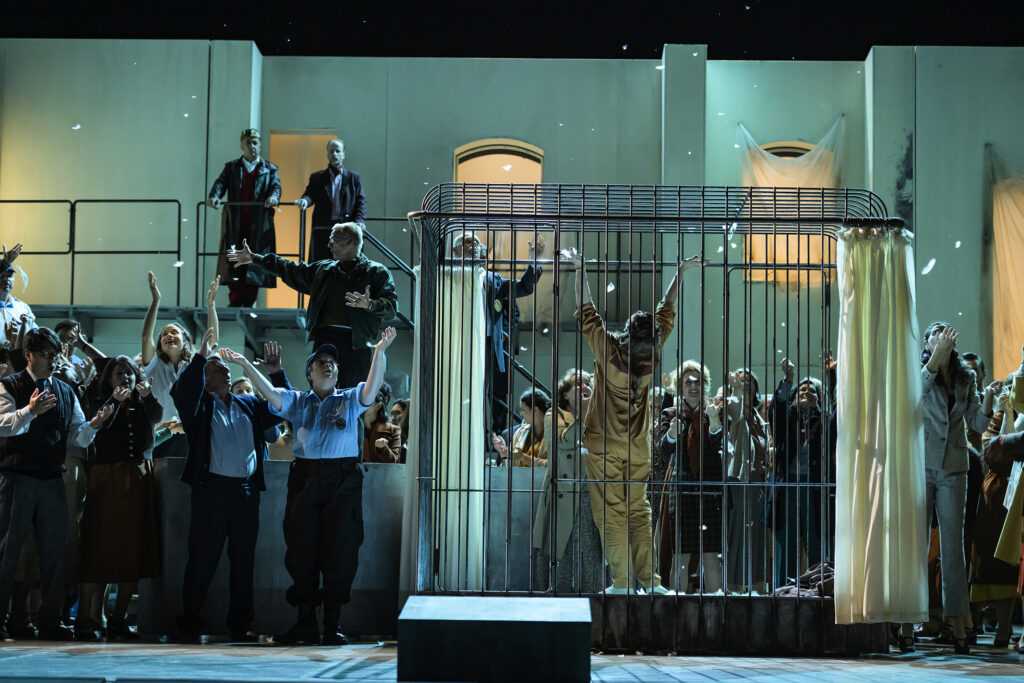

Elsa also appears during the ethereal prelude to Act I, harassed by Ortrud’s husband, Telramund. When she rebuffs him, his men lock her in a giant birdcage. The intrigue begins. Brabant is leaderless, and Telramund’s advances toward Elsa were, of course, also his path to the throne.

To settle the question of succession, König Heinrich enters from the auditorium, complete with hiking gear—pulling Brabant’s crown from his rucksack. The conflict also divides the Brabantians themselves. Telramund accuses Elsa of murder, while Ortrud, with brazen haste, attempts to crown herself.

Standing in for the ill Ewa Vesin, Khatuna Mikaberidze presents a commanding and authentic Ortrud, who keeps her predatory birds—stuffed—locked in cages. A quote by C. G. Jung in the programme offers insight: where a person dies, there remains only the unfulfilled, “hovering” wish to still live. Hence, the soul is a bird. A moving and reconciling concept for this bird-themed Lohengrin.

Brunel’s strength lies in the psychological depth he grants every character, striving to illuminate their motivations. Lohengrin, therefore, is not merely a one-dimensional, warmongering saviour who leads Brabant’s leaderless people into battle, but a man suffering within himself. A particularly striking image shows him at the beginning of Act III as a broken figure with black swan wings—which could also be a vulture costume. Elsa sees this and pities him. But in the following bridal chamber scene, he only makes things worse. Elsa no longer believes a word he says—with good reason. She has sensed his dark origins, has seen his suffering. The dramaturgical intensity here is scarcely surpassable.

Moreover, during the bridal chorus “Treulich geführt, ziehet dahin (Faithfully guided, we tread the path),” Brunel has women lining up to report for duty at the front. The chorus’s words are thereby transformed into a militaristic call to arms—especially after “general mobilisation” is announced in Act II.

Lohengrin is sung by Maximilian Schmitt with a dark timbre and an always secure, precisely articulated voice. His Grail Narrative, underscored by a repetition of Gottfried’s murder (as in the prelude), is not performed in the usual angelic, high head tone but in a deeply grounded register—perfectly in keeping with the director’s interpretation. Shavleg Armasi delivers a radiant, finely nuanced, and textually clear König Heinrich, who also acts with professional conviction. Excellent!

Equally compelling is Viktorija Kaminskaite’s interpretation of Elsa: lyrically flowing and delicately nuanced, though she occasionally lacks the expressive dramatic despair the role demands. Her transformation—from blindly obedient girl, to accomplice in Lohengrin’s war rhetoric, to ultimately redemptive, empowered woman—is made vividly clear through her performance and costume changes: starting with a pure white dress, shifting to half and then full brown (a reference to Adolf Hitler’s Eva Braun), and finally transforming into a red military uniform (costumes by Nathalie Palandre).

Peter Schöne gives the Herald with expressive and clear baritone; Grga Peroš impresses as Telramund with his dark, well-grounded tone.

The choruses, prepared by Lorenzo Da Rio, lack initial cohesion due to their bold placement on either side of the orchestra pit, but soon convince with warm tone and engaging presence.

Sadly, the orchestral performance lacks interpretative clarity throughout the evening. While some passages are interesting, the overall musical tension, thematic continuity, and precision in articulation are inconsistent and fail to form a compelling arc across acts.

How this production ends shall not be revealed here. Suffice it to say: the conclusion is convincing, coherent with the direction, and offers a compelling summation of a significant interpretation of this problematic work.